Fighting for the future: When revolutions become civil wars

My Book Review of Dan Edelstein's The Revolution to Come: A History of an Idea from Thucydides to Lenin in the TLS

I’m excited to share that I’ve had my first essay published in this week’s edition of the Times Literary Supplement: a review of Dan Edelstein’s subtle and wide-ranging work, The Revolution to Come: A History of an Idea from Thucydides to Lenin (Princeton, 2025).

Revolution is a concept I have been thinking about for some time. My fear of it—if I might admit to such a thing—started with my reading of Edmund Burke (1730–1797), the reforming Whig who was wary of the limitless violence that the pursuit of an ideal society invites into our sense of justice.

That question—Are we really living through revolutionary times?—is obviously pressing when we consider Artificial General Intelligence. It is equally important before our consideration of the new despotisms we are encountering in Western liberal democracies and abroad. We carry the baggage of the last two thousand years of history with us into both crisis points. But particularly the last 250 years history since the French Revolution: which spawned a range of historical and philosophical assumptions about progress that are still retracting our lives today. These are dealt with in Edelstein’s book and, at some length, in my review of it.

The full review can be accessed here.

For now, here are some of the closing lines of the review:

Edelstein argues that we are now living in a new era of revolution. “We are moderns”, he writes, “living in a world made by ancients.” We are obsessed with the future while remaining essentially unaltered in our nature. We are as imperfect as the Greeks of Thucydides’ day. And we should be equally wary of ourselves. Unlike the ancients, we praise revolution when we should fear it. Unlike the moderns, we’ve given up on the idea of radical change. Put depressingly: we’re all talk. So, Steve Bannon can boast – and hastily retract – that he’s a Leninist who wants to destroy the state. Bernie Sanders can chatter in the language of popular uprising while serving as a senator.

Edelstein brands this the “third act in the history of revolution” – a state of vapid de-definition in which revolution is hollowed out. At the end, his argument shifts into a normative register that doesn’t quite suit him as a historian. He urges us to defend the mixed constitution, Polybius’ great inheritance. He worries about the “democratic backsliding” we are witnessing around the world – what he calls a “silent revolution”. “Perhaps the greatest revolutionary threat today”, he suggests, “is one that dare not speak its name.” Here, his otherwise splendid global history contracts and suddenly feels pointedly – parochially – American. Those on both sides of the political spectrum contribute to the risk, he claims. Believing that human beings can be perfected, and that disagreement itself can be ended, he warns, is a wish that makes “everything worse”. Left-wing radicalism, he writes, and even milder forms of liberal technocracy, will enable right-wing dictators to trash constitutions harder.

Or are left and right inadequate to describe what’s happening, and is another “real” revolution in play, animated by the same zealotry as the French one in 1789, but driven this time by tech-baron elitists, from Peter Thiel to Sam Altman? For who are they, if not the new future-obsessives, scanning the horizon for signs of that dawn which has bewitched revolutionaries from Robespierre to Mao?

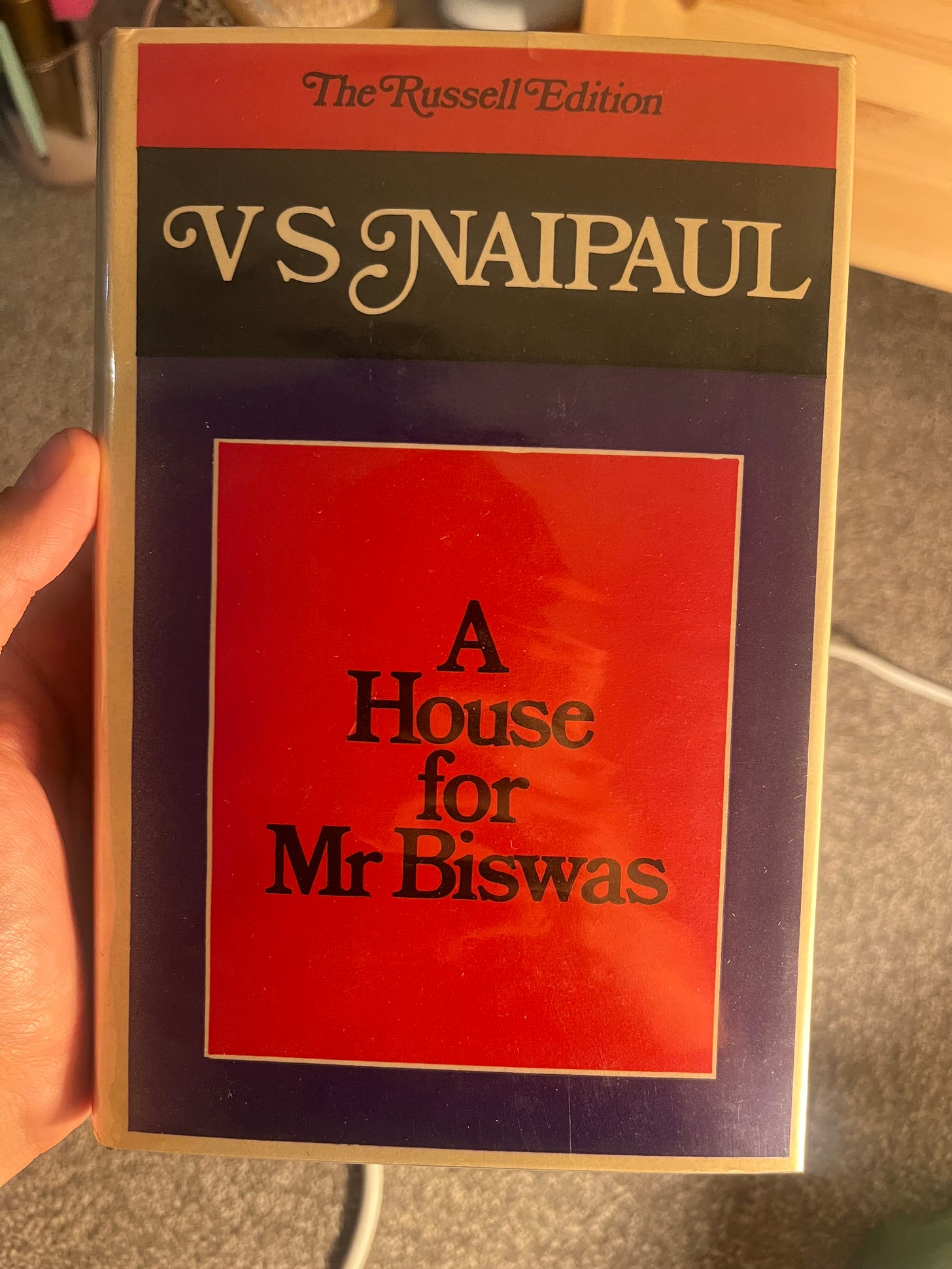

Being published in the TLS has meant a good deal to me. The TLS is one of London’s great literary magazines, with a noble history that includes the work of many writers I admire, from Orwell to Naipaul. I decided to celebrate by buying the rare first-edition signed copy of V. S. Naipaul’s A House for Mr Biswas (his first novel) that I’ve been eyeing in Oxford for over a year. Naipaul, the Trinidadian-Indian writer who went on to win the Nobel Prize, came up to Oxford in the 1950s with nothing but a manic compulsion to see himself as a “writer.” Heeding both Naipaul’s ambition and his warning—that one becomes such a thing by first pretending to be it—I thought I’d buy the book.