#2 Reflections on the 2025 Australian Federal Election

And what it means for some themes in politics I have long been thinking about

I must confess, these early reflections may not be terribly revealing; they are not intended to be a definitive take on the election. They are unashamedly partial to my particular commitments back home and certain themes in Australian politics over the past few years that I have been trying to reconcile: the place of First Nations people in our nation; and the opportunities for reform leadership on both sides of politics. I’m living abroad in England and can’t claim to be caught up in the circumstances of this Australian Federal Election. Still, I can’t help but reflect on my country’s future under a re-elected Labor Government, which—I will state at the outset—is a positive result in my book.

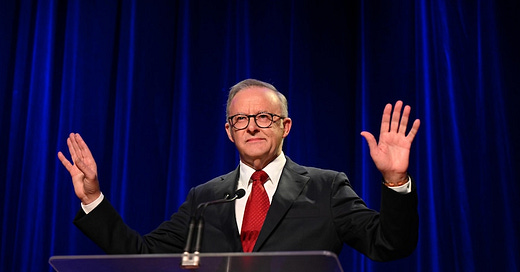

As of early Sunday morning, the ABC’s results indicate that Labor has gained an even greater majority in the House than they could have expected—85 out of the 150 seats up for grabs. On the current count, this leaves the Coalition with a paltry 37, and is historic for two reasons: it marks Labor’s highest two-party preferred vote in its history; and is the Liberal Party’s lowest ever primary vote. Australian election campaigns feel increasingly presidential. This was Albanese’s triumph, the result of a consistent campaign on-message, and Dutton’s extreme embarrassment—he lost his own seat of Dickson to Ali France, a third-time contender, disabled single mum whose son tragically died of Leukemia last year. In a rare moment, Dutton showed great magnanimity in his concession speech to both Albanese and France.

Yet these numbers don’t tell the full story. A third of Australians voted for other parties: the Greens, the Teal Independents (light, liberal-style moderates committed to gender equality, integrity, and climate action), community-rooted independents like Dai Le in Fowler, and nativist options like One Nation—the old poison in the Australian blood. All this reflects a wider trend in democratic politics away from major parties towards the margins. The Coalition lost votes to the Left more so than the far Right. Neither One Nation, nor Clive Palmer’s American knock-off party, Trumpet of Patriots, mattered so much electorally in the end.

The Liberals would be mad to lurch rightward after this loss. But the need to lean into their liberal tradition was also the lesson of their 2022 defeat. How many times can one ward against the madness of repetition?

They have been thrown out of Tasmania (does this at least have something to do with the state’s local issues around salmon farming regulation?). Left even poorer in Victoria (Josh Frydenberg is likely relieved he didn’t try to take back Kooyong from Monique Ryan). And in Queensland, where people historically vote conservative, Luke Howarth lost Petrie, as Dutton, aforementioned, was betrayed by the people of Dickson! Outer suburbia, it seems, no longer guarantees LNP fortunes, as the Coalition hoped it did.

The reason might be, as Redbridge pollster Kos Samaras recently reminded us, that most of Menzies’s “forgotten people” are now dead, and that “Howard’s Battlers” are in retirement. In Australia, this shift is being propelled forward by the demographic forces of the future: Millennials and Gen Z. Voters under 40 are now the greatest determiners of the country’s electoral patterns. Yesterday, they voted in droves for the Labor party and those smaller progressive parties like the Greens whose preferences lurch to Labor. In this, Abbie Chatfield and her Instagram audience now play the same role of the silent (or not so silent) majority that Howard’s battlers did in the late 90s and early 2000s. The Coalition, however, utterly failed to appeal—or even placate—this younger generation shaping Australia’s electoral patterns. They overwhelmingly lean Left, though not all young people, it must be stated, are progressive by default. (Interestingly, while the Greens’s overall vote went up nationally, they lost both the seats of Griffith and Brisbane won in the “Greenslide” of 2022: Max Chandler-Mather, a young MP who has long agitated on housing reform on the national stage, has been ousted.)

Who is fit to restore the Liberal party now? Or is it all over for them, organisationally speaking? The party seemed moribund ideologically a long time ago. Dan Tehan and Susan Ley are woefully uninspiring leadership candidates. Andrew Hastie, a former SAS Captain, may offer a more coherent model of conservative politics. He seems to be a person of integrity, and one of the few Liberal Shadow Ministers returned with a vote count in the 40s. Perhaps the task will fall to him to develop a strategy capable of winning over this younger generation.

Why did the Coalition lose so badly, then, even when, in late 2024, they looked poised to take government during what is still a difficult economic period for Labor? Clearly, Australians did not want Dutton. I definitely didn’t. I grew up under his watch as Immigration and then Defence Minister, and witnessed the sense of personal vocation he seemed to draw from inflaming Howard-era immigration politics in the age. Dutton’s attitude towards refugees, and his treatment of the Biloela family especially, remains haunting. But perhaps more than anything else, it was that Australians sought stability in the global age of Trumpian insecurity. Incumbency, in reverse of its customary force, is an advantage, at least for now. Albanese was trusted to govern through uncertain times. Dutton was not worth the risk. I expect that it’s already become a well-worn talking point that this election shows that Australians didn’t want to invite Trump-style politics at home. Thankfully, we are set up institutionally to resist populism through our compulsory and preferential voting system. But we must always remain vigilant of the health of our parties internally.

Comparisons will be drawn for days with Canada, where Pierre Poilievre, the leader of the Conservatives, was primed to gain government before Trump started his insane war on Canada. Like Poilievre, Dutton lost his seat from protest. The parallel is helpful—even moving for those resisting global movements inspired by Trumpism—but only to a point. Canada is in a far more precarious situation than Australia, where their proximity to—and relationship with—America is concerned. Australians may not like Trump, but again, let’s not take the analogy too far. Where Trumpism did show up in our campaign, it did so rather half-heartedly, pathetically: Dutton’s last-ditch culture war about “Welcome to Country” ceremonies; Jacinta Price’s brief appearance in a MAGA cap.

Which reminds me. A telling moment during the election coverage was the ABC’s Sarah Ferguson’s terse exchange with Jacinta Price, Senator for the Northern Territory. There was Price, at home in Lingiari, framed in cinematic style by the camera alongside her family and husband—the scene looked partially funereal. I couldn’t help but feel some sense of sadness for Price: For someone trapped so bitterly within the language of spite and politics. She claimed that the Labor victory would lead to further ideological narrowness in the way that Canberra policy treats Indigenous Australians, who would find that their real experiences would be ignored by bureaucrats. (The very opportunity to correct this, of course, was lost with the Voice’s defeat in October 2023, a defeat which Price helped ensure.) Still there was a kind of loneliness draped about her.

… yes, I think that’s what unsettled me most about tonight’s victory speeches. Watching Albanese’s victory oration, I thought back to 2022, when in the same hall at Canterbury-Hurlstone Park RSL Club, he opened his win with dead-set moral certainty: 2022 would be the year of History! Albanese invoked the Voice to Parliament as the promise that would complete the Australian compact and fulfil the mission of the Labor Party: “On behalf of the Australian Labor Party, I commit to the Uluru Statement from the Heart in full.” And so, he promised his crowd and country, to death-defying applause.

I’m not blaming Albanese for the defeat of the Voice—he always seemed to me genuinely and compassionately committed to it. But we cannot ignore that this is the first federal election since the Voice’s defeat, a fissure moment in Australian national politics, akin in some ways to Brexit in the United Kingdom. What stands out to me is that many of the same voters who, just recently, resoundingly returned a Labor government to power, dishonouring the Coalition, are also among those who voted to reject the Voice. Australians, as this election shows us, are willing to vote socially democratically when it comes to their material concerns but are not as ready to confront historical injustice. This is understandable, especially in the midst of a cost-of-living crisis. Material needs are top of mind when people vote.

What’s strange, though, is how last night both Penny Wong and Anthony Albanese, in their speeches, sought to incite the same elation around Labor’s connection to Indigenous peoples that they had before the Voice’s defeat, back when they celebrated their 2022 election victory. This time, however, their appeal had to be slightly adjusted. Let’s hear from Wong first: “Thank you for believing in the power of this great nation. The power in our 26 million people from more than 300 ancestries. And from the oldest continuing civilisation on the planet. And I acknowledge the traditional owners.” Her voice lifts here, as if she’s about to continue, but the thought never comes—or at least we never hear it. There’s an awkward pause, followed by, “Friends, we love this country.”

What did she leave unsaid? Albanese does something similar: there is no mention of the Voice or its defeat, even though it was the major promise of the 2022 election. Only victory and glory take centre stage on a night like this. He thanks Australia for “a chance to serve the best nation on earth. And I acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which we meet.” Again, note the rapturous applause: “And I pay respects to elders, past, present, and emerging, today, and every day.” Then, the party faithful roar in response, for these words reject the Liberal Party’s politicisation of Welcome to Country ceremonies. “Yes. Today, the Australian people have voted for Australian values—for fairness, aspiration, and opportunity for all…”

Listening to these well-meaning words, I couldn’t help but feel that the fate of Aboriginal people had been abandoned, at least in any material sense, and ritualised before that applause. They were reduced to an abstraction on stage, acknowledged as part of the Australian story, yes, but only as a formality before the real political speech began. I don’t want to criticise Labor unfairly; I know they have little choice but to proceed in this way, given the logic of politics (after the defeat of the constitutional Voice, a legislated Voice is nearly politically impossible). I admit that I am reading my own commitments into this narrative. But that’s precisely the point of this confession. What strikes me is how quickly politics can pivot from the experience of moral defeat to new proclamations of victory. That shift—so swift, so silent—says something about what politics does to us, doesn’t it?

Perhaps the Voice was a flawed reform, perhaps the campaign had shortcomings. Either way, the Referendum defeat, combined with the results of yesterday’s election, signals a clear rejection of cultural politics in favour of addressing immediate economic concerns. The cost of living, global insecurity—these are what mattered to Australians at the ballot box. And it makes perfect sense that they did. But there’s another, sad element to this that I feel compelled to state and lament. Now that we can speak of these events in the past tense—we are, after all, now in another election cycle—I see the defeat of the Voice as representing a broader cultural settlement. The Australian compact has been shrouded behind the veil of a failed Referendum. In October 2023, the Australian people tacitly affirmed that Aboriginal people will not be central to ur national identity moving forward. Yesterday, we confirmed that our own material concerns, to be addressed by a Labor majority Government, are what matter most.

So yes, this election is a condemnation of Peter Dutton. It’s a rejection of Trump-style politics in Australia. But it’s also a return to material politics over all else, with the belief that in order to make that work for us, we must move on from cultural issues. There is much wisdom in this thought. But the greatest losers in this shift are those who must accept the final settlement that emerges from the last two years of Australian politics—a settlement that diminishes the role of Aboriginal people within the Australian compact. It remains to be seen what material improvements can be delivered for Aboriginal people in this new age of material elections, beyond merely invoking their story as a means of placing ourselves within their narrative.

Hi Jack I liked your thoughtful review of our election. These issues have been troubling me for a year or more. Trump capitalised on the failure of liberal politics in the US but others tried to here and in UK and Canada. My essay The Regressive Turn of Progressive Politics examines how modern progressive movements, once rooted in expanding liberty and opportunity, have increasingly embraced moral absolutism and elitist narratives that alienate the very communities they claim to champion. This essay explores the cultural backlash now unfolding, tracing its origins to a loss of humility, institutional overreach, and the betrayal of liberal democratic principles. My fear is that such a defeat of the a Liberal Party will sweep any examination of these deeper philosophical ideas away. What are your thoughts? Cheers Russell